IGDC PhD students Stella Nwawulu Chiemela, Luqman Muraina, and Aasim Sheikh give an overview of the IGDC Research Away Day.

The decolonisation imperative

In recent years, there has been a growing demand within the fields of international and global development to decolonise the knowledge production process. This imperative arises from critical examinations of the historical power imbalances and epistemological biases that have shaped the field. In the intricate landscape of development research, the spotlight increasingly shines on a fundamental yet often obscured aspect – the concept of positionality and its inherent power dynamics. This scrutiny becomes imperative in an era marked by a heightened presence of diverse voices and a growing acknowledgment of the lingering impact of colonialism on research practices and relationships. The recognition and comprehension of these dynamics transcend mere scholarly pursuits, they represent a pivotal stride towards cultivating research practices that embody the principles of justice and inclusivity.

The IGDC’s research away day offered a valuable opportunity to explore the urgent requirement for decolonising development research, tackling obstacles, and collaboratively shaping a path that aligns with the wider goals of inclusivity and justice in the field. Against this backdrop, the concept of positionality and the inherent power dynamics within development research come under scrutiny.

The imperative to decolonise development research necessitates a profound recognition that the process of conducting research cannot be divorced from broader global socio-political and historical contexts. It is imperative to acknowledge that research endeavours are not conducted in isolation, but rather are deeply intertwined with power dynamics, cultural biases, and historical legacies. In his groundbreaking work on Orientalism, Edward Said established the foundational framework for interrogating asymmetries of power within the realm of scholarly inquiry. The author posited that the Western perspective frequently depicted the Eastern world through a distorted prism, influenced by preconceived ideas and prevailing power differentials. Said’s profound insights resonate deeply within the ongoing discourse, serving as a poignant reminder that the realm of research is inherently imbued with subjectivity and lacks the elusive quality of neutrality.

It must be underscored that researchers must not only scrutinise how power is wielded but also how it can be resisted within the research context. By acknowledging their own positionality and being mindful of power dynamics, researchers can begin to decolonise development research.

It is important to also note that research cannot occur in a vacuum. Researchers bring their unique identities, experiences, and worldviews to their work. Recognising this is the first step towards decolonisation. Understanding how one’s background may influence the framing of research questions, data collection, and interpretation. To decolonise research, researchers must critically reflect on their biases and preconceptions and actively work to mitigate their impact on the research process.

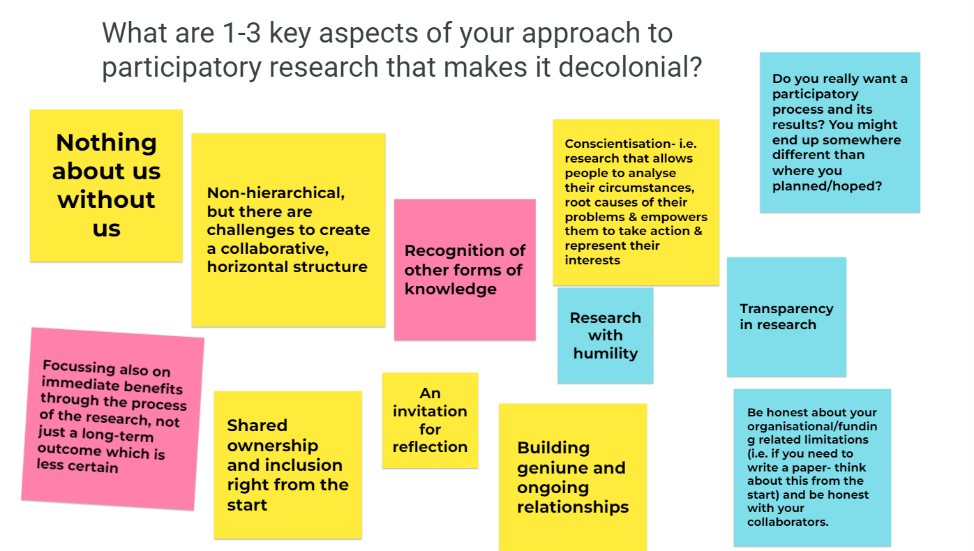

Power imbalances are also inherent in research, often stemming from historical structures that prioritise certain voices over others. To decolonise, researchers must strive for more equitable partnerships with the communities they study. This involves engaging in meaningful collaboration, sharing decision-making power, and valuing indigenous knowledge. By shifting power dynamics, research becomes more ethical and respectful of diverse perspectives.

With these considerations in mind, we aim to engage with postcolonial and decolonial scholarly work to discuss how researchers’ positionalities and power dynamics can be navigated to pursue equitable research partnerships with local researchers, people, and communities.

The role of positionality in decolonising research

The research process and the relations fostered by it are not solely driven by the search for objective facts and data. Rather, it is intricately shaped by the researcher’s positionality, encompassing their unique identity, personal experiences, and worldview. This acknowledgement serves as a critical starting point in the journey towards decolonising development research. Crucially, we must also acknowledge that researchers are not mere detached or neutral observers, but rather active participants who inevitably bring their subjectivities to the table. This recognition is essential in understanding the multifaceted nature of the research process and the potential impact of researchers’ personal perspectives and biases on the outcomes and interpretations of their studies.

By acknowledging the inherent subjectivities of researchers, we can gain a deeper understanding of the complexities involved in knowledge production and the need for reflexivity in the research endeavour. The recognition of personal bias is not a weakness but should be regarded as an essential aspect of the current discourse, necessitating careful consideration. In The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon, an influential philosopher on postcolonialism, stressed the importance of recognising one’s background in the pursuit of true liberation. In the context of development research, this liberation translates into understanding how a researcher’s background influences the framing of research questions, the process of data collection, and the interpretation of findings. Critical reflection and positionality is, therefore, the cornerstone of decolonisation. Researchers must interrogate their biases, preconceptions, and the inherent power dynamics at play.

Researchers must also strive to “unlearn” ingrained colonial perspectives, as urged by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak in her work, Can the Subaltern speak?. This unlearning involves a conscious effort to mitigate biases and acting as the subaltern ‘spokesperson’ during the research process. It is a continual process that demands introspection and a commitment to challenging entrenched norms.

Navigating power imbalances to seek equitable partnerships

The presence of power imbalances within the realm of research is an undeniable reality, deeply rooted in historical frameworks that have consistently favoured specific perspectives from certain regions while marginalising others. In order to embark on the process of decolonisation, it is imperative for researchers to actively pursue and cultivate more equitable partnerships with the communities they study. This transformative approach challenges and dismantle the prevailing power dynamics that have historically marginalised and silenced these communities.

By engaging in collaborative and reciprocal relationships, researchers can foster a more inclusive and just research process and relationships that attribute history, agency, and knowledge systems to the communities involved. This shift towards equitable partnerships not only enhances the quality and validity of research outcomes, but also contributes to the broader goal of decolonizing knowledge production, enhancing research impacts, and promoting social justice.

A renowned postcolonial theorist, bell hooks advocates for an engaged pedagogy that disrupts traditional power relations, fostering a more democratic and participatory learning environment. This perspective can be applied to the research landscape, thereby urging researchers to seek equitable partnerships with the communities they study. This involves engaging in meaningful collaboration, sharing decision-making power, and valuing local knowledge. By shifting power dynamics, research becomes more ethical and respectful of diverse perspectives.

In the scholarly discourse of Linda Tuhiwai Smith, equitable partnership is elucidated as a paradigm that prioritises the sharing of power rather than its exertion. It demands meaningful collaboration, equitable distribution of decision-making and authority structures, and a sincere appreciation for local knowledge. This ethos challenges researchers to relinquish the traditional role of the expert and embrace a collaborative methodology that duly recognises the agency and expertise of local communities.

The way forward

Decolonising research not only transforms the dynamics within the research process but also contributes to the broader goal of addressing historical injustices perpetuated by the colonial cum white superiority gaze. Audre Lorde posits that there is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives. Lorde compels us to transcend the limitations of single-issue activism and embrace a more inclusive and comprehensive framework for social change. Development research, when decolonised, becomes a collective endeavour to create space for marginalised voices and rectify the historical imbalances inherent in the continuing colonial legacy. By centring marginalised perspectives, this process seeks to redress the power imbalances that have long characterised the development field.

The call to decolonise research practices is still gaining momentum and challenging the academic community and institutions to reassess their methodologies, ethics, and practices. It requires a commitment to dismantling structures that perpetuate inequality and embracing an ethos of respect for diverse perspectives and pluriversality. In this ever-evolving landscape of global development research, the journey towards decolonisation is a collective and transformative process. As we heed the call to decolonise, we embark on a path that leads to a brighter, fairer, and more respectful world for development research. The destination is not just a theoretical construct but a tangible reality worth pursuing, step by step, in the pursuit of justice and equity in the research paradigm. Join us on this transformative journey – the destination is worth every step.

About the authors

Luqman Muraina started his Global Development PhD programme at IGDC, University of York, UK in 2023. He completed his MA and B.Sc. Sociology programmes from the University of Cape Town (UCT), South African and Olabisi Onabanjo University, Nigeria, respectively. Luqman researches decolonisation, higher education, African politics & development, black feminism, and social movement. He also advocates on racism and injustice issues, including Black/African and Palestinian causes.

Stella Chiemela is a doctoral student at IGDC University of York. She holds a BAgric in Agricultural Economics from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria, and an MSc in Agroecology and Sustainable Development from Mekelle University in Ethiopia. Her research specialisation is in interdisciplinary studies, with a major focus on natural resource and environmental-related issues.

Aasim Sheikh is an interdisciplinary PhD researcher in Politics and Sociology at IGDC, University of York. After completing his LLB (Hons.) (University of Bristol) he graduated with two masters degrees – an i-LLM/LPC in Legal Practice (The University of Law) and an MPA focusing on International Development (University of York). Aasim’s research brings together Global Production Networks and Social Movements through a Cultural Political Economy lens to empirically study their interactions within the overlapping networks of Ivory Coast Cocoa Production and Fairtrade Advocacy.