By William Harnden (Managing Director, Connected Development)

Working for a range of international development organisations over the past 15 years, there has been one consistent issue which has been a challenge for all of them. Local people: the national staff, government members, and communities that are the target ‘beneficiaries’ of internationally funded programmes, often don’t feel that interventions are really designed for them. This lack of ‘local ownership’ means that programmes may run for years, but their impact eventually comes to an abrupt halt when external funding stops.

I have also learned over the same period that there is no quick fix for this challenge. The scale of humanitarian and development challenges in the world, the speed of responses needed in emergency situations and the requirement of international organisations to provide secure working environments for their staff are all factors working against local ownership.

Connected Development emerged from a conversation between a group of grantmaking organisations (donors) and civil society based organisations (CSOs) that had been struggling to locate each other in a sector dominated by the larger institutions. What if local ideas, emerging from community initiatives and built up within civil society, could then be taken on by regional and national governments? This ‘bottom up’ approach to development tends to be pushed to the margins when most funding is handled by a few major international aid agencies, sent to internationally staffed country offices, with the local organisations simply acting as their ‘implementing partners.’

Over the past 5 years, we have been gradually building a small, interactive network of CSOs and donors based in over 15 countries. By acting as a ‘hub’ for both sides, we have been able to initiate several mutually beneficial partnerships through a mixture of knowledge sharing and service provision (Connected Development is a social enterprise). Meanwhile, we have been continuously learning about the different methods used to achieve local ownership and sustainability within local communities. One thing has quickly become clear: there are several different models which can work.

Local leadership

The first member organisation to join Connected Development’s network in 2019 was a community based organisation focused on creative education for displaced communities from Myanmar. Kick Start Art is run by John Khai, an artist from Chin State, the poorest province in the country. John now works with a team of artists from a base in Mae Sot, a Thai town 4km from the border with Myanmar.

Over the past 5 years, Kick Start Art has provided supplementary teaching for children of families that have migrated into Thailand for safety or for work, taught at schools inside Myanmar, and run activities in camps for refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). What has been impressive about their model, operating with local teams – each of whom have directly experienced the challenges that they are addressing on a daily basis – is how adaptable the organsiation has been.

Whether facing school closures during the coronavirus pandemic or responding to the 2021 coup and ongoing conflict in Myanmar, Kick Start Art has been able to adapt its programmes quickly. For many families arriving from Myanmar, unable to register in an official camp or migrant school, John and his team have been the first organisation to provide support to them as they attempt to re-start their lives.

John Khai, Director of Kick Start Art, Teaching a class in Chin State, Myanmar, 2018

Community ownership

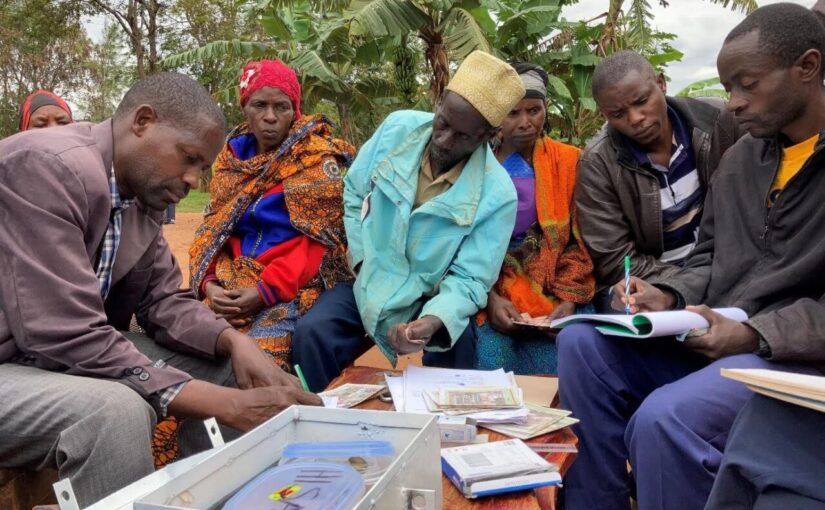

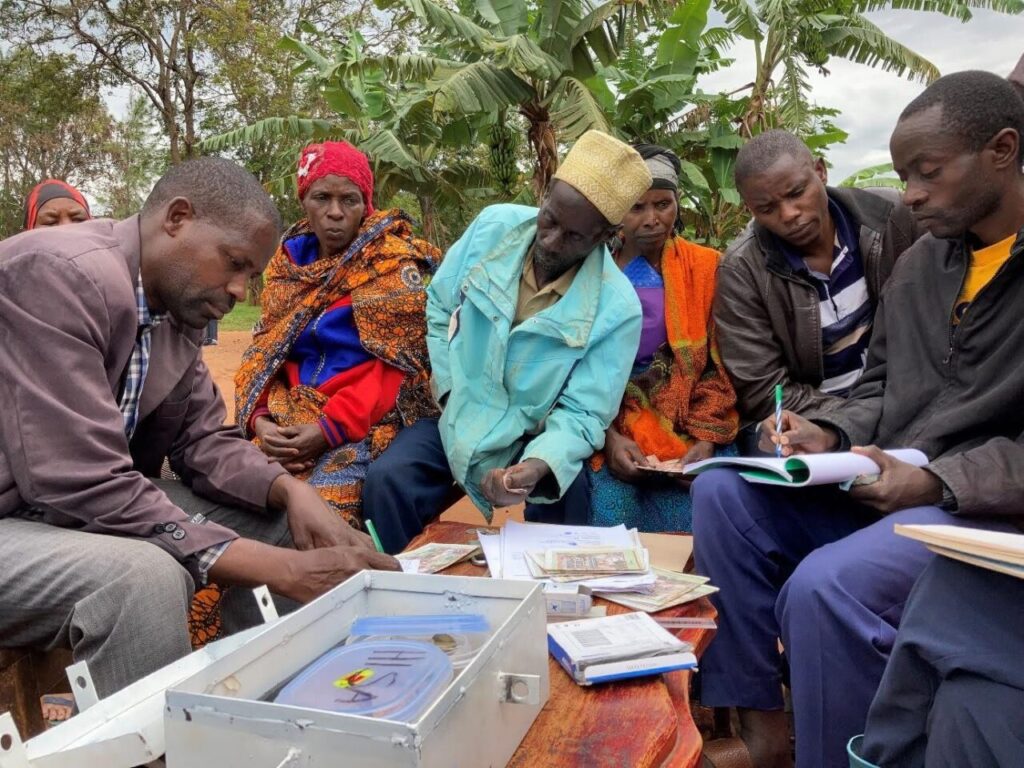

The Development Support Initiative (DSI) is led by a small group of Tanzanian professionals, each of whom has experience working with international NGOs or within the private sector. Their focus area is the remote, rural Kagera region of the country, tucked between Lake Victoria to the East, Uganda to the North and Rwanda to the West.

Shimba Lusela and his colleagues identified that the communities in this region had become isolated from government and international aid programmes. Starting their initiative with a community-led needs identification exercise, DSI launched its first programmes in 2020. Since then, it has built all of its work around the principle that everything they do must involve the active participation of the communities benefiting.

What has been notable from this approach, delivered by Shimba and local community workers, is that following initial training, the community sees the project as theirs. Microcredit training has resulted in community groups learning how to pool funding and create individual and group enterprises. Once a Development Support Initiative project is completed, the community continues with what they started, independently of external support.

A Village Community Bank (Vicoba), in the Kagera Region, Tanzania, 2022

Social enterprise

In the far south of Madagascar, a local organisation called Tatirano is working hard to address the challenge of drought by actively promoting rainwater harvesting. Their Director, Harry Chaplin, is an engineer from the UK, but the remainder of the team of more than 80 are all local Malagasy staff, who oversee an annual programme of building and maintaining water collection systems at schools and community centres.

In a step away from dependence on external grants, Tatirano recently constructed a large rainwater collection, treatment and bottling centre. Rainwater is now sold to local residents and businesses in and around Fort Dauphin, with profits used to subsidise the installation of new systems in poorer, more remote areas.

What is impressive about the Tatirano social enterprise model is that in addition to generating revenue to fund its own projects, the water sales also encourage the wider consumption of filtered rainwater in society. In a country which faces the dual challenge of monsoon rain and drought at different times of the year, Tatirano’s idea is to identify sustainable local solutions that rely on natural resources to tackle the issue.

A Tatirano ‘agent’ managing a rainwater collection point in Fort Dauphin, Madagascar, in 2023

These are just three case study examples of civil society based approaches to development challenges which build upon locally available human and natural resources. What each has managed to achieve is a strong level of local ‘ownership’: the element so often missing from mainstream development programming. As we gradually build up our knowledge sharing network at Connected Development, we aim to continually share insights into innovative approaches like these. As a collective community of practice, we hope that some of these models might be taken up by policymakers and replicated on a wider scale.

Author biography

William Harden, a University of York graduate, has worked in international development for the past 15 years. He has worked within the UN system, International NGOs, and the UK charity sector. In 2019 he launched Connected Development to strengthen cooperation and to promote the undervalued work of local development actors within the sector. William has lived in Timor-Leste and Thailand for half of his career and regularly travels to the field to meet local and international humanitarian and development agencies.