IGDC member Helen Elsey, Margaret Nampijja and Linda Oloo present findings from their new article published in Frontiers in Public Health

Back in 1978, Castells wrote: “the subordinate role of women … enables the minimal maintenance of the city’s housing, transport and public facilities … because women guarantee unpaid transportation, because they repair their homes, because they make meals when there are no canteens…. because they look after others’ children when there are no nurseries. … if women who ‘do nothing’ ever stopped to do ‘only that’, the whole urban structure as we know it would become completely incapable of maintaining its functions” (Castells, 1978:177–8).

Almost 50 years later, the invisibility of women’s work has not gone away, in fact, with increased urbanisation in low and middle-income countries, women’s unpaid and low-paid roles continue to keep cities functioning yet are frequently overlooked and undervalued. This is particularly clear when it comes to childcare. More women, particularly from low-income households, are working long hours outside the home often in informal employment. By migrating to the city, many parents no longer have the benefit of nearby extended family able to help look after their pre-school children.

The combination of urbanisation, women’s working patterns and changing social structures has created a childcare vacuum. The World Bank estimates that 40% of all pre-primary children globally need, but do not access, childcare (World Bank 2019). Our research, with partners the African Population and Health Research Centre (APHRC) in Nairobi, Kenya found the situation to be particularly acute in deprived urban neighbourhoods such as the informal settlements or slums where over 60% of Nairobi’s population live. The lack of public sector or affordable private sector childcare in the city means that parents, predominantly mothers, face the impossible choice of either taking their babies and young children to work with them, leaving them at home with siblings – often resulting in girl children being taken out of school – or using the many informal ‘baby-cares’ that have sprung up to meet demand.

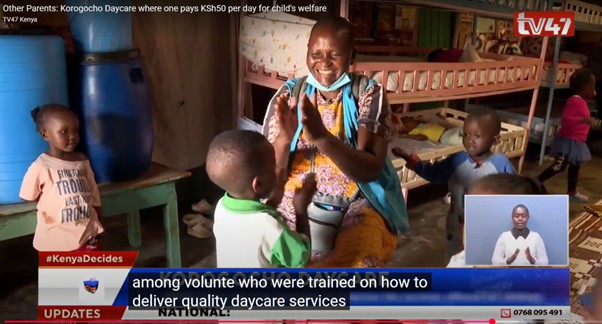

The informal baby-cares are normally a one or two room home within the informal settlement where a woman will look after up to 20 pre-school children and babies. Our research in two informal settlements found 129 baby-cares, but only 12 of these (9%) had received any support or training and that quality of care in terms of hygiene, safety and responsive caregiving were severely limited (Nampijja et al 2023). Despite providing a crucial service to keep the city functioning, these informal baby-cares have fallen between the cracks of siloed policies and programmes. With education departments focusing on school-age children, and the maternal and child health programmes dominating the health sector’s energies, early childhood development and particularly, day-care struggles to find it’s policy home. Our review of national and county level policies in Kenya found limited focus on early childhood development particularly in terms of ‘responsive care’ and ‘learning through play’ which are all key parts of WHO’s Nurturing Care Framework (WHO 2018).

Our feasibility work in Nairobi clearly showed that programme responses do not need to be complex or resource intensive. With funding from the British Academy our team were able to work with the childcare providers in the informal baby-cares, as well as community health teams, mums, dads and families to develop a simple intervention that existing community health teams can implement as part of their routine work. Following training on early childhood development, community health promoters (CHPs) facilitated groups of baby-care providers using a ‘community of practice’ approach to learn and share good practice in responsive care, child health, hygiene and safeguarding. They then included the baby-cares in their routine visits to check how they were doing as well as making sure the children were up-to-date with their immunisations and other child health programmes. We developed a training manual for use by the community health teams to enable other teams across the city to implement the intervention.

A key factor in enabling the delivery of the intervention was the decision by Nairobi City County local government in 2021 to pay a monthly fee and provide health insurance coverage for the CHPs. While this is still low (3000 Kenyan Shillings ~£18/month), it does mark a shift in recognition of the role of CHPs in underpinning community health through their vital, but rarely lauded, role in delivering immunisation, nutrition, malaria and other core public health campaigns. Following four months of implementation of the intervention in 64 informal baby-care centres in two informal settlements in Nairobi, we found not only that delivery was feasible and appreciated by baby-care providers, CHPs and parents, but also there were significant improvements in the knowledge and practices of the baby-care providers.

Throughout our study, the APHRC team worked closely with Nairobi City County officials, continually raising the need for quality childcare, the role of informal baby-cares and the profile of early childhood development. Presenting the evidence from our study as well as allowing baby-care providers and parents, particularly mothers, to share their experiences of attempting to provide the best for their children in such challenging conditions has way key to gaining buy-in from the local government. To do this effectively our team have learnt that we need to look beyond the siloed and traditional focus of research and policy. Resources are always a challenge; however, it is the invisibility of ‘women’s work’ both within and beyond the home, particularly in caring for young children that has been the overriding challenge to finding solutions. As researchers we can have a powerful role in making the invisible visible and enabling the voices and experiences of economically and socially excluded communities to be heard.

The project was covered by Kenyan TV station TV47, you can see the video here.

About the authors:

Helen Elsey is a Professor in Global Public Health in the Hull and York Medical School. Her research focuses on strengthening urban health system in Africa, Asia and the UK. With British Academy funding, she has worked closely with the African Population Health Research Centre, APHRC – based in Nairobi – to co-create and evaluate community health system support for day-care centres in informal settlements.

Margaret Nampijja is a developmental psychologist with a medical background, focusing on early child development (ECD) research. Based in APHRC’s the Maternal and Child Wellbeing (MCW) Unit since February 2019, she is engaged in several ECD projects including assessing the feasibility of providing day-care centres at work places and its impact on women’s economic empowerment and child growth and development.

Linda Oloo is a Research Officer whose work focuses on the neurological and developmental outcomes of young children living in resource-poor urban settings and pastoral communities in rural Kenya. Dr Nampijja and Prof Elsey co-lead the Nairobi Childcare Community of Practice study and Linda Ollo led the implementation and qualitative research within the project.

References

Castells, Manuel (1978) City, Class and Power (London: Macmillan)

Nampijja M, Langat N, Oloo L, Amboka P, Okelo K, Muendo R, Elsey H. (2023) The feasibility, acceptability, cost and benefits of a “communities of practice” model for improving the quality of childcare centres: a mixed-methods study in the informal settlements in Nairobi. Front Public Health. 2023;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1194978

Abboah-Offei, M., Amboka, P., Nampijja, M., Owino, G., Okelo, K., Kitsao-Wekulo, P., Chumo, I., Muendo, R., Oloo, L., Elsey, H., (2022). Improving early childhood development in the context of the nurturing care framework in Kenya: A policy review and qualitative exploration of emerging issues with policy makers. Frontiers in Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1016156

World Health Organization (2018) Nurturing care for early childhood development. https://www.who.int/teams/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-health-and-ageing/child-health/nurturing-care care for early childhood development