In 2022, the Cockpit Country, a unique karst landscape in west central Jamaica, was declared a Protected Area. This followed decades of conflict over conservation of this area of high biodiversity between a range of stakeholders – the government, international organisations, environmental groups, and local communities. My article ‘Conservation and Conflict in the Cockpit Country, Jamaica, 1962-2022’, examines threats to the area’s biodiversity and attempts to conserve it, from Jamaica’s independence in 1962 to the declaration of the Cockpit Country Protected Area. One of the main threats facing the area was bauxite mining. Here I explore how island-wide protests following the issuing of prospecting licences culminated in the declaration of the Cockpit Country Protected Area but argue that this has not removed the threat of bauxite mining because of government’s dependency on the sector as a major foreign exchange earner.

Save the Cockpit Country campaign

Bauxite deposits were first discovered in the Cockpit Country in the 1950s but the ore was of lesser quality than found elsewhere (Jefferson 1972: 153). When high-quality ore in other parts of Jamaica began to dry up in the 1990s, mining companies turned to the Cockpit Country. It was after one company sought renewal of its prospecting licence that environmental groups learned that government had allowed prospecting in the Cockpit Country. In August 2006, they set up the Cockpit Country Stakeholders’ Group (CCSG), a coalition of environmental groups, the Maroons – descendants of escaped African slaves, who established free communities in the western part of the Cockpit Country –, other local communities, Local Forest Management Committees, journalists, and academics, and started the ‘Save the Cockpit Country’ campaign, which relied heavily on social media and demanded that government revoke the licences and declare the Cockpit Country a no-mining area (Fuentes-George, 2016).

In 2007, the government suspended the licences and agreed to consider prohibition of mining in the Cockpit Country but only after a study of the area’s boundary (Gleaner, 9 March 2007: A2). A boundary study group was set up, which proposed a commonly-understood boundary – the ‘ring road’ that had linked British army camps in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and covered parts of the parishes of St Elizabeth and Trelawny. Public consultation about this boundary, which due to lack of funding did not take place until 2013 (Gleaner, 11 July 2013: D7), suggested five other boundaries, each allowing for more or less mining. The boundary proposed by the Jamaica Bauxite Institute, for instance, denied access of 10 million tons of ore, but the one proposed by the CCSG denied access of 300 million tons (Gleaner, 21 August 2015: A6).

Permission for reproduction granted by Dr Susan Koenig.

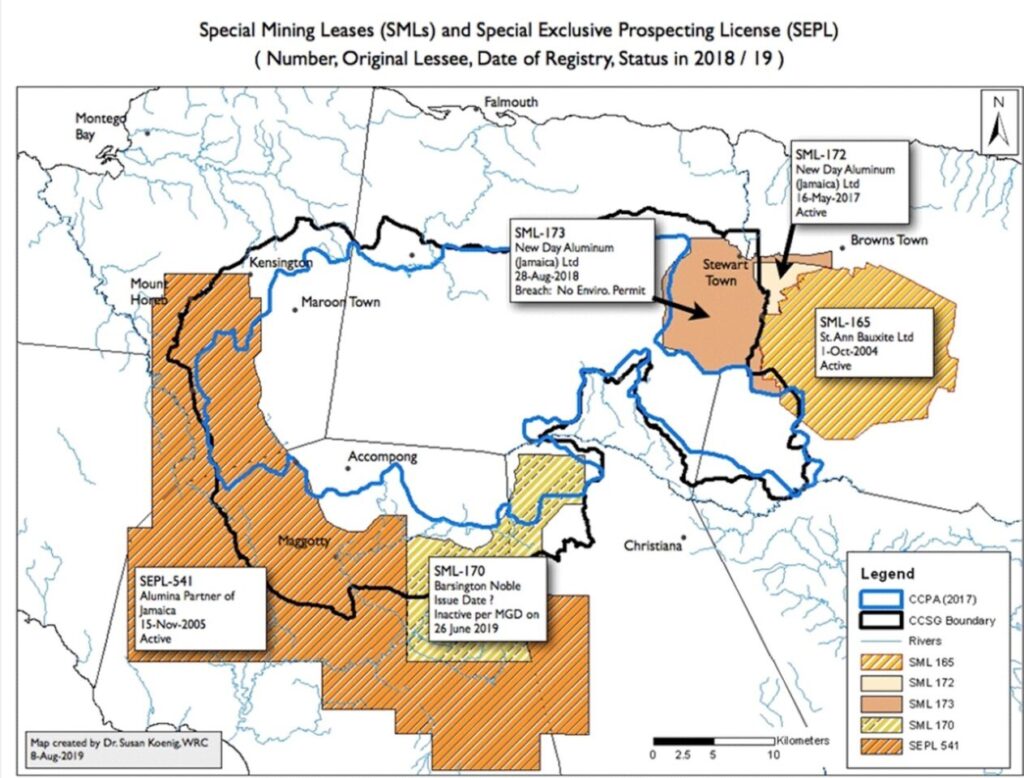

In 2017, government finally settled on a boundary, announcing that 74,726 hectares would become the Cockpit Country Protected Area (see figure). Bauxite mining and other unsustainable activities would be prohibited, and existing Special Mining Licenses (SMLs) and Special Exclusive Prospecting Licences (SEPLs) would be modified if they fell within the area. The proposed protected area excluded important cultural and historical sites and did not include the full Cockpit Country aquifer. The area was 32 per cent smaller than that advocated by the CCSG and did not have a buffer zone so that mining could be allowed up to the boundary, affecting watersheds and the livelihoods of farmers just outside the boundary (Gleaner, 3 December 2017: G2). The government’s boundary decision was largely driven by its belief that bauxite was key to the Jamaican economy. In 2004, it had acquired a 51 per cent share in Noranda, a bauxite-exporting company that mined in St Ann, a parish partly located in the Cockpit Country (JET, 2020: 4 and 40). In 2004, Noranda was granted SML 165, which partly fell within the boundary of the proposed protected area (see figure). And in 2014, Noranda was granted SEPL 578 for a site that also partially fell within the proposed area but this licence had expired in June 2016.

It took until March 2022, following a long ground-truthing exercise to determine the final boundary, before the Cockpit Country Protected Area was finally gazetted (Jamaica Gazette 2022). Yet a year earlier, the government had already undone its promise to prohibit mining by granting JISCO Alpart Ltd an SEPL that replaced SML170 (see figure), parts of which fell within the Cockpit Country Protected Area (Gleaner, 5 November 2021: A4). It is also still unclear how the area will be managed and what activities other than mining will be disallowed.

Another campaign

The lack of a buffer zone allowed government to grant Noranda SML173 in 2018 for a site just outside the Cockpit Country Protected Area (see figure), which would give it an estimated US$150 million in revenue per year. When Noranda started mining before an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) had been approved, the CCSG started another public campaign. In December 2020, a public meeting to discuss the EIA was held, broadcast live on TV and radio and streamed on various platforms(Conrad Douglas & Associates Limited, 2023). This was followed by a three-week public consultation during which the Jamaica Environment Trust, Jamaica’s the leading environmental organisation, organised a virtual town hall meeting and various organisations made submissions (petchary 2020).

After various revisions, the EIA was finally approved in February 2022 but for a slightly different area because government had taken 6,000 hectares off SML173, part of which fell within the Cockpit Country Protected Area. This, however, did not constitute a victory for the CCSG because Noranda was promised 6,000 hectares to mine elsewhere and the approved EIA left many significant issues raised in the public consultation unaddressed, such as risks to underground water supplies (petchary 2023).

The fight continues

The Jamaica Environment Trust has continued to campaign for the protection of the Cockpit Country through social media, research, and lobbying (Jamaica Environment Trust). The Southern Trelawny Environmental Protection Agency, another environmental group, has taken recourse to legal action. In 2021, it filed a claim to the Supreme Court with Clifton Barrett, a farmer from Trelawny, relating to SML173. Several months later, nine residents from St Anne filed a claim relating to SML165, SML172, and SML173. Both claims sought to overturn the licences, arguing that they violated the residents’ constitutional right to ‘enjoy a healthy and productive environment, free from the threat or injury from environmental abuse and degradation of the ecological heritage’ (Jamaica, 2011). The St Ann residents also applied for an interim injunction until their case was heard, which was granted in January 2023 in respect of SML 173 but not for the other two licences as they were inactive.

Noranda appealed the injunction, claiming that the residents were not at risk of “irreparable harm” because they lived some distance from the mining site and the permits included “enhanced protections”. As the majority shareholder, the government strongly supported the company, fearing an injunction could result “in negative growth” (Gleaner, 27 March 2023: A1 and A3). In June 2023, the Court of Appeal lifted the injunction. (Gleaner, 10 June 2023: A3).

The government has been unable, however, to stop the two constitutional claims, which will be heard together. The Attorney General tried to remove the Southern Trelawny Environmental Agency from the case, claiming it did not have legal standing to commence a constitutional claim. The Supreme Court rejected his claim, which the Attorney General then appealed. In June 2024, his appeal was dismissed on the grounds that Jamaica’s charter of fundamental rights and freedoms allows any person or organisation to bring cases on behalf of persons whose rights are being violated (Gleaner, 16 June 2024: A5).. To date, the Supreme Court has not given a date when it will hear the constitutional claims.

The nine St Anne residents also took their case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. In June 2022, Malene Alleyne of Freedom Imaginaries, submitted an application on behalf of them and other ‘Afro-descendant families from peasant communities in St Ann’, living near the bauxite mines (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2022), asking that the Jamaican government be required to adopt ‘the necessary measures to protect the rights to health, personal integrity, and life’ of the beneficiaries. The Commission found there was a prima facie case and in November 2022 issued a precautionary measure to that effect. So far, the Jamaican government has not responded to the Commission nor has it contacted the beneficiaries, which illustrates that it values short-term economic gain over long-term environmental gain. A Supreme Court ruling in favour of the Southern Trelawny Environmental Agency and St Anne residents, however, may force it to change its priorities.