Faculty Engagement Manager Ned Potter offers ten tips for academics getting started on the Bluesky social network

Many academics and researchers have chosen to leave Twitter / X due to recent events, and one of the places they’re sharing ideas instead is Bluesky. For those not familiar with this platform, it is extremely Twitter-like in look and feel but with exponentially less toxicity – and it has recently doubled its number of users in a very short period of time, in fact adding more than 1 million users in the last week alone.

There is a growing University of York community on Bluesky (more on how to find this community below), and if you’d like to be part of it read on: this guide is for you. It’s worth noting that the official word from the University is that staff are welcome to set up and maintain personal social media accounts related to their work, provided that their use conforms with the University’s social media policy – best to ensure you have read the policy before setting up a new Bluesky account.

Throughout this guide I’ve quoted various York academics, and it seems appropriate to start with this advice from Dr Richard Carter (School of ACT):

Don’t be afraid of starting out again. If you have a sizeable following on Twitter-X, the prospect of shifting to a significantly smaller audience on BlueSky might appear very discouraging. Nevertheless… rebuilding on a fresher, far less toxic platform offers us a chance to reconnect with the core audience of professionals that we always intended to reach and be in dialogue with.

Here, then, are ten top tips for those ready to rebuild.

1. Fill out your profile BEFORE you start following people

A trap many ‘Newsky’ people fall into is looking up their peers and friends and following them on the platform, before setting up their own profile: picture, bio, link etc. The issue is that accounts with generic avatars and no biography or introductory text are often perceived as likely to be bots, so users not only eschew following them back but they may even automatically block – meaning the chance to engage in dialogue is gone.

Put in a bio of some sort, and an avatar: it doesn’t have to be a picture of you. As Dr Jeremy Moulton (Department of Politics and International Relations) says: “…immediately write your bio and then post an ‘I’m here!’ post that sets out your interests and what’s brought you onto the app. For me, it was to say I was interested in environmental politics and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, for example.”

2. Adapt for – and enjoy – the lack of algorithm

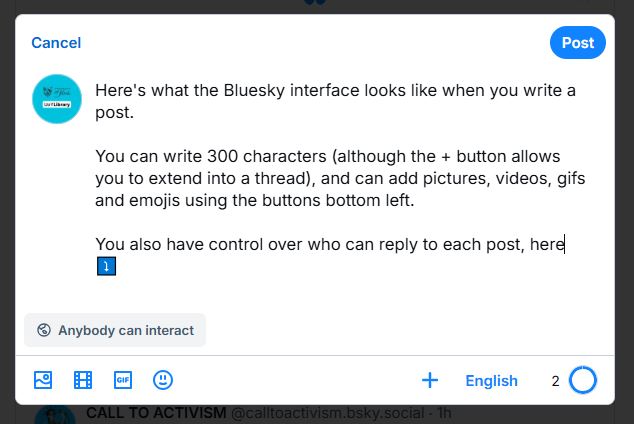

Bluesky is very Twitter-like in lots of functional ways: you can post up to 300 characters at a time, you can repost, you can Like, and so on.

The crucial difference is the lack of algorithm – the lack of endlessly auto-refreshing content, showing you things you didn’t ask to be shown. Bluesky’s default ‘Following’ feed is simply the posts from the people you follow, in reverse chronological order. That’s it.

It takes some time to readjust to proactively seeking out posts and people to engage with, but it’s well worth doing. When you’re new, if you don’t get out there and follow a bunch of people, your feed will be completely dead; with that in mind, as Dr Lucy Grigoryan (Department of Psychology) says: “It’s worth following a lot of people – more so than on twitter, it really changes the whole experience” – so how do you find people to follow?

There are several ways but let’s start with the most York-specific.

3. Follow the University of York Bluesky Starter Pack

A ‘Starter Pack’ is a curated group of users on Bluesky, which you can follow all in one go with one click. This is a really nice feature of the platform, and the first one we’d recommend following is the brand new, expanding-all-the-time University of York starter pack, which you’ll find here!

Consisting primarily of academics at York, along with some professional services staff and departments who have created presences on the platform, this pack is the easiest way to connect with colleagues from the off. Two things are worth noting here: you can follow the whole pack and then unfollow / weed as you go along (you’re not obliged to follow all of the accounts, forever), and if you would like to be added to this pack please let us know! The easiest ways to get added is to ask the library on Bluesky itself (@uoylibrary.bsky.social) or send me an email (ned.potter) if you’d prefer.

4. Find other useful starter packs

“One of the best things you can do when starting out on BlueSky is to curate your experience from the get-go: look up different feeds of interest, follow those you’re interested in, follow anyone interesting ‘they’ are following, and take advantage of the new starter packs to rapidly follow the activities of people in related areas of interest / work. It will take a little while to organise, but it’s worth it,” says Richard Carter.

As well as the York starter pack there’s an entire Directory of Starter Packs available, allowing you to search by keyword to see if your discipline is represented. If you’re still looking for people to follow after searching the directory and taking all of Richard’s advice above, you can use Skyfollower bridge to follow the same people on Bluesky you used to follow on Twitter if you wish to.

5. Get up to speed with custom feeds

Whilst a Starter Pack is a useful tool, it is also a fairly blunt one – you follow a group of users united under some sort of thematic umbrella, but you see all of their posts (about any subject). A slightly more subtle device, well worth getting on board with, is the Custom Feed: a curated set of posts on a theme, rather than merely a set of users, which you can view whether you follow the people posting to the Feed or not.

Posters can use emojis or hashtags to tag posts to appear in the feed, depending on how the feed is set up; usually you will need to ask the creator of the feed to add you to the list of eligible posters if you wish to actively participate, but anyone can view and follow a custom feed.

Prof Colin Beale (Department of Biology) says “Finding, following and requesting being added to feeds that are relevant to your research and then tagging posts for those feeds appropriately is very helpful” and in fact using custom feeds was the most often cited piece of advice amongst the academics I spoke to about Bluesky, with Dr Emilie Murphy and Professor Jennie Batchelor among others flagging it.

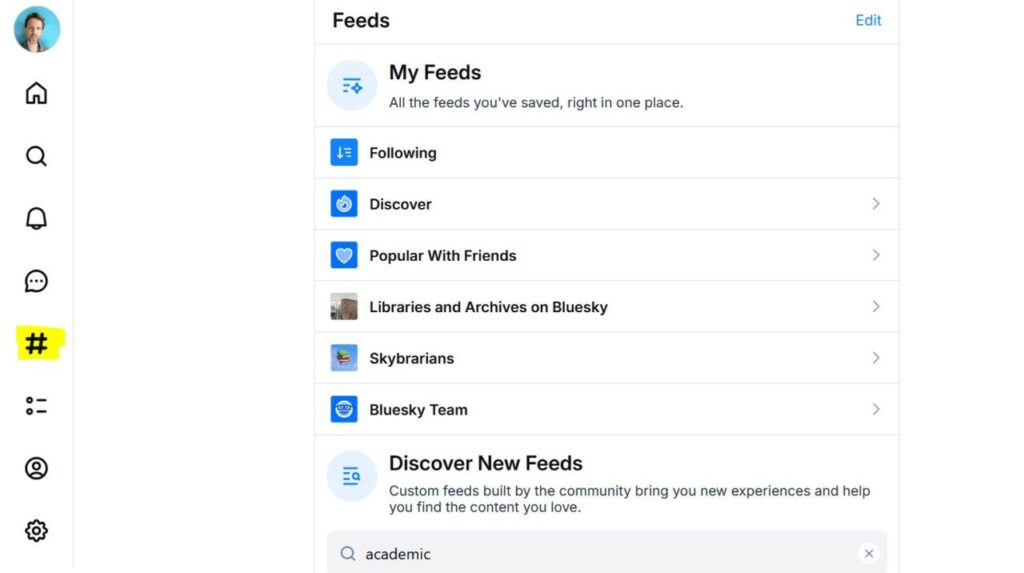

Pavlos Vasilopoulos (Department of Politics) specifically recommends the polisky feed for those interested in political science; there’s an AcademicSky feed for general HE chatter, a PhDSky feed for and by PhD Students, and so on. Search for feeds in Bluesky via the Feeds menu (hit the # button down the left-hand side of the home screen on desktop, or top right of the home tab on the mobile app) and you’ll see any feeds you already follow, plus a search box under ‘Discover New Feeds’.

6. Be proactive. Like, reply, engage

All those clichés about how you get out what you put in really apply here. You have to go beyond broadcasting and truly engage: reply to other people’s posts, join in conversations, cultivate discussion. One the tips from Dr Terry Hathaway (Norwegian Study Centre) is simply “…engaging in conversations rather than focusing on posting some branded message out into the void.”

Dr. Sophie Coulombeau advocates a mix of the professional and the personal if you feel able: “…blend self-promotion (‘Thrilled to announce…’) with other stuff around hobbies, interests, and boosting the work of others, if you feel comfortable doing so.”

7. Don’t just post links to your articles, post mini-threads highlighting your findings

More than one academic I spoke to advocates using Bluesky to discuss research papers rather than merely linking to them. Here’s how Colin Beale puts it: “As a general rule posts that just say “We’ve got a great new paper here, read it” don’t really work – but explaining in a short thread the key findings is a much more effective way of engaging.”

8. The follower numbers are lower but the engagement is higher

Several users who maintain presences on both X and Bluesky report that engagement is much higher on the latter: in fact a comparison by Andrew Dressler found engagement was 10 times greater on Bluesky:

Furthermore Katharine Hayhoe reported that not only was the level of engagement considerably higher on Bluesky, the nature of the responses was much more positive too.

In short, don’t be put off by the idea of starting again with a smaller network.

9. Make the most of Bluesky’s powerful moderation tools

Good moderation and the ability to control who you interact with has been baked into Bluesky from the start, and it makes such a difference. Dr Sabine Clarke (Department of History) says “I do a lot of pre-emptive blocking. When people follow me now who appear to have no interests in common, or seem a bit random, I just block them.”

When you block someone they are gone completely: if they leave a comment on your post and you block them, you won’t see the comment and no one else will see the comment either. If someone Quote posts you and you don’t like it, you can detach your post from theirs so they’re no longer associated. Not only that, you can subscribe to blocklists (e.g. this one) which really do starve problematic groups of the oxygen they need. It’s basically the opposite of Twitter.

As well as the nuclear block option, you can also use the mute function to moderate your own experience of the platform. Richard Carter says, “…if there are topics and discourses that you could very much do without seeing regularly, it can be an invaluable tool. I’ve compiled a veritable ‘devil’s dictionary’ of words to help bring a sense of personalised calm to my various feeds.”

10. Bluesky can be better than Twitter, but give it time

Bluesky is often seen as a Twitter replacement but it doesn’t have to be only that – it can take the good things from that platform and leave some of the bad things behind to make something better. In particular, engaging the trolls and quote-posting the terrible takes – all of that is not necessary on Bluesky, especially when the Block button is so effective.

The accessibility is better too: I’d recommend accessing Settings, find the Accessibility section, and toggle the switch marked ‘Require alt-text before posting’ and you can create accessible content every time. You can also add alt-text (and indeed captions) to videos – finally a social network which offers this… Here’s a great resource on how to write alt-text descriptions, if you want to brush up.

As we’ve seen above the engagement rate is already higher than Twitter – and the academic and Higher Education communities are really starting to build up on the platform. A strong York presence will only enhance that. You may not get instant results on Bluesky, but it’s worth putting in the time. And remember, if you do end up joining the platform after reading this, let us know so we can add you to the York starter pack… Join us!

Bonus tip for departments: speak to Central Communications before you start!

If you are considering creating a new Bluesky account to represent a School, Department or other University Service or subsidiary, please get in touch with the University’s Central Communications team before you get started at communications-support@york.ac.uk. There’s more information on what the Communications team will cover with you on the University’s Social Media For Staff page, including account ownership and security.